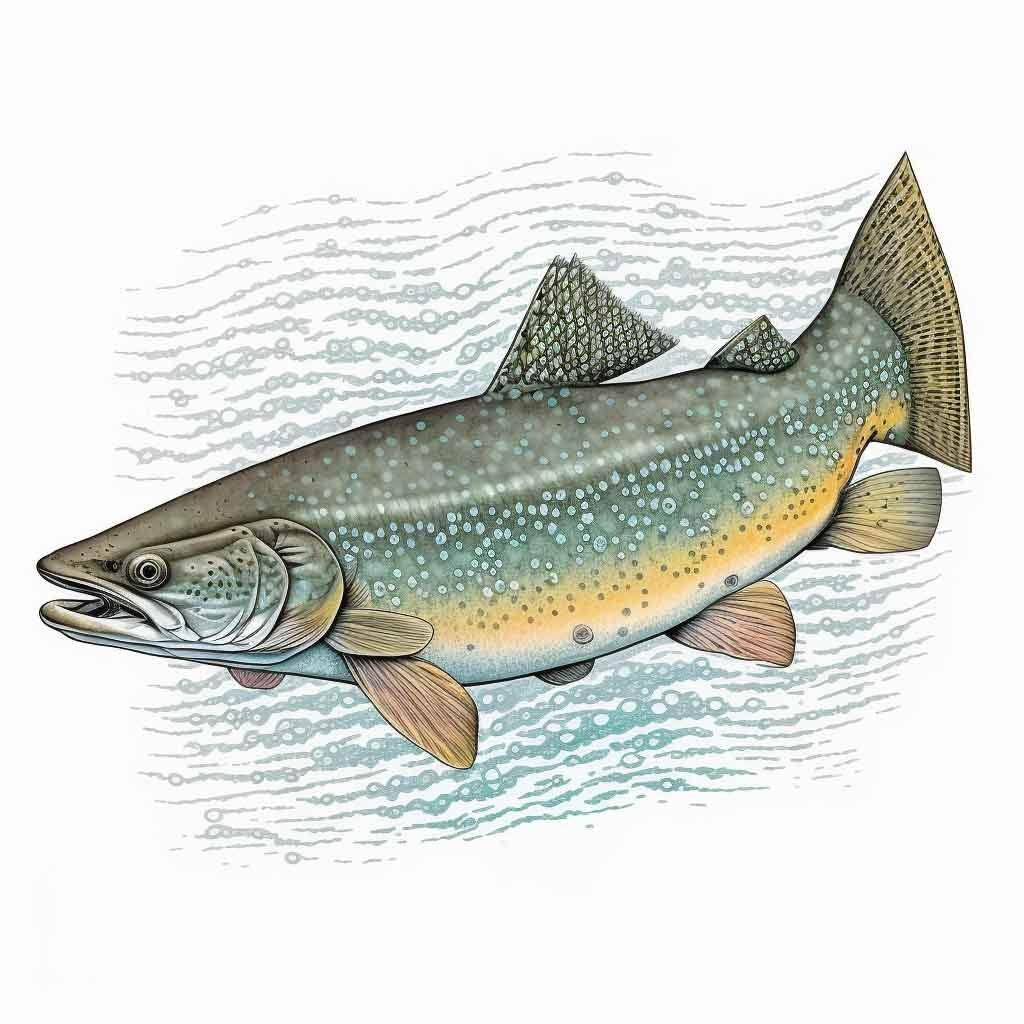

Lake Trout (Salvelinus namaycush)

Lake trout, along with brook trout, belong to the “char” sub-group of salmonine fishes that is distinct from the “true” trout and salmon. Lake trout inhabit deep, cold lakes, and are strongly influenced by annual temperature events within a lake. During winter, when most lake waters are a uniform 0 – 2° C, lake trout can range throughout a lake and prey upon small fish and bottom insects. In late April or early May, lake trout feed actively upon minnows, crayfish, and abundant insect larvae that are active at that time of year in shallow areas. When warm surface water becomes established during June in nearshore areas, lake trout are forced into deep, cold waters far below the surface where prey is relatively sparse. As summer temperatures cool off in September, the warm upper lake cools off and lake trout once again hunt regularly in more productive surface waters.

Lake trout spawn at night on rocky shoals in the fall, usually during late October or early November. Fertilized eggs settle within rocky crevices where they remain until hatching about four to six months later in late February to April. Athough spawning shoals are frequently located in shallow areas less than ten feet below the surface, deep-spawning lake trout are found within Seneca Lake and are believed to have occurred within the Great Lakes.

Growth rates of lake trout vary widely from lake to lake, depending on whether they feed upon fish or generally feed upon crustaceans or insects. Plankton-feeding lake trout seldom get much larger than one to two pounds, even though fish of this size often can reach ages of 20 to 30 years. However, lake trout that feed upon fish can reach huge sizes greater than three feet in length and 30 pounds, though such fish are never abundant.

Lake trout were originally found in more than 80 New York lakes, including the Finger Lakes, Lake Erie, Lake Ontario, Lake Champlain, Lake George, and many Adirondack lakes larger than 50 acres. Yet despite their widespread recognition as a top lake predator, lake trout populations in most New York waters are declining or threatened. For example, Great Lakes lake trout were completely eliminated from Lakes Erie and Ontario due to predation by non-native sea lampreys during the 1950s and 1960s, and self-sustaining lake trout populations have not been successfully re-established despite 30 years of stocking efforts. For the past decade, small numbers (e.g. less than 30) of naturally-produced lake trout have been observed annually in Lake Ontario surveys, but these numbers pale by comparison with the hundreds of thousands of hatchery-produced lake trout stocked annually into this lake.

Finger Lake lake trout populations exhibit similar difficulties due to sea lampreys — which are now controlled by chemical treatment in tributary streams of Cayuga and Seneca Lakes — and a thiamin-deficiency-related reproductive failure, called “Cayuga Lake Syndrome” or “early mortality syndrome.” Fish susceptible to this syndrome die shortly after hatching, but fry from identical egg sources survive and exhibit normal behavior when treated with the vitamin thiamin. Thiamin is now added to water supplies to maintain the viability of hatchery-raised lake trout, which sustain Cayuga Lake and Lake Ontario lake trout fisheries. Keuka Lake, Skaneateles Lake and Seneca Lake lake trout populations still sustain large populations of naturally-reproducing lake trout.

Adirondack lake trout populations have been reduced by over-fishing and their inability to compete successfully with non-native smallmouth bass that typically reduce the abundance of native forage fish in near-shore waters. In small lakes with abundant smallmouth bass, lake trout feed primarily on plankton and insects and exhibit slower growth than in lakes without bass.

Leave a Reply